Though my mother’s family did not leave Europe until 1939, they knew for years before Nazi jackboots thundered through Vienna that they would have to leave their beloved city, and antisemitism was to blame. Kristallnacht had not yet clarified the Jews’ position in Austria when my grandfather began to plan the family exodus.

The early warnings were sometimes subtle, sometimes overt but rarely violent. Until a sunlit, sultry day – July 15, 1927, when violence disrupted a family idyll and set forces in motion that impelled their emigration.

Papa had been in France on an extended business trip, and he had not been home for his birthday the day before, so the family designated the 15th a holiday, which they set out to enjoy at their favorite park overlooking the city. Their day would celebrate Vienna as much as their patriarch.

They boarded a tram that took them to the medieval Höhenstrasse, and from there, they transferred to a bus that carried them through the Grinzing, past the charming Heuriger taverns, into the Vienna woods, and to the top of the Kahlenberg.

When they arrived on the mountain, a procession of mummers, along with boys and girls in costumes singing a Polish hymn, was preparing for a processional in honor of the relief army Poland’s King Jan III Sobieski sent to save Vienna from the Ottoman siege in 1683.

“See?” Said Papa, an emigree from a shtetl in Eastern Poland. “The Austrians love us Poles.”

His family laughed. Being Jewish and being Polish was not the same thing. But neither the Poles nor the Jews were popular in the post-Empire days of sprouting Austrian nationalism. The parade made them giddy.

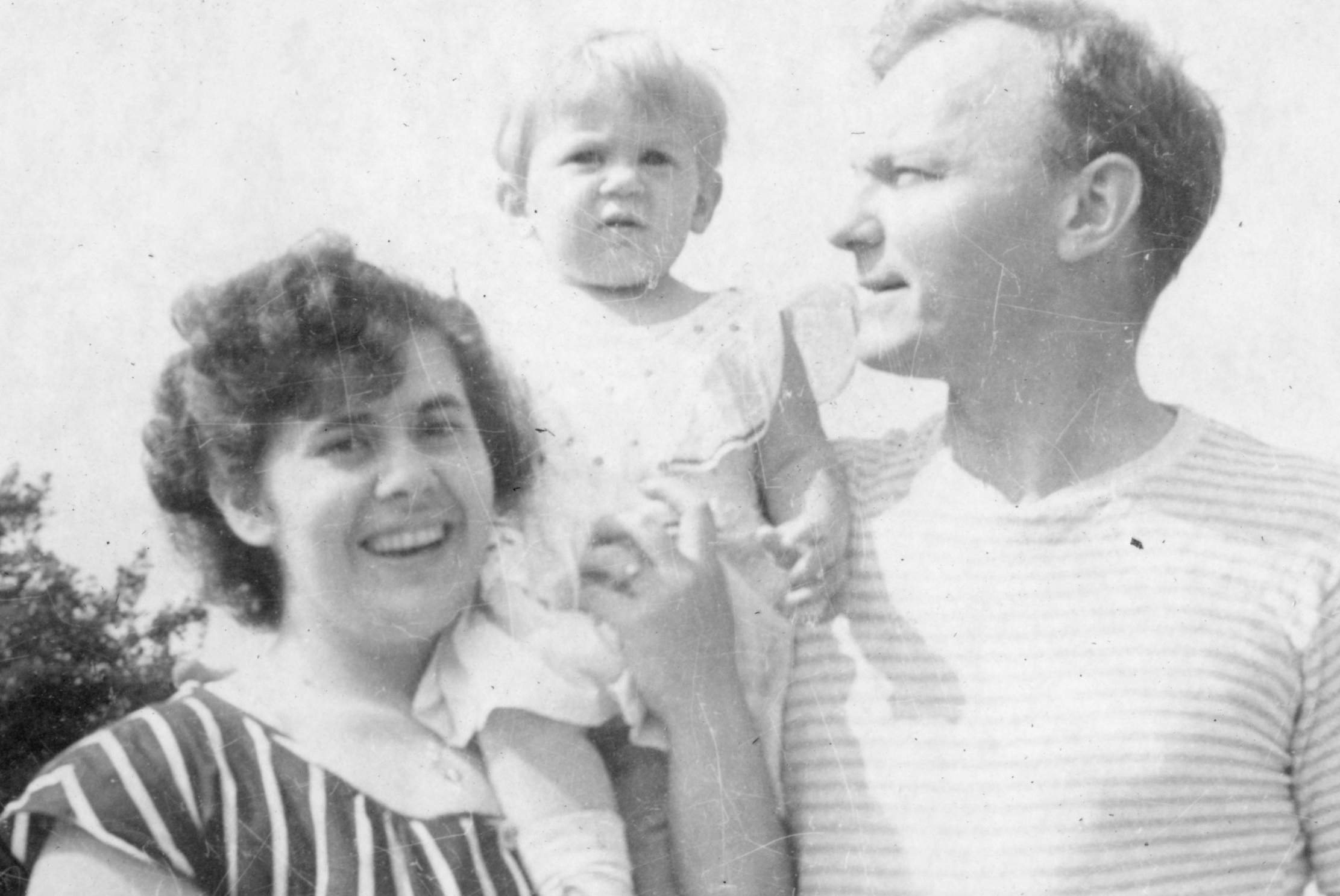

My mother Charlotte, age three, and her sister Thea, age four, pretended to be bunny rabbits, hop-dancing to the processional music. Baby Ruthi cried for a bottle and tugged at the bandages covering the surgery she had had behind her ears several days before. Herma, maturely nine, crossed her arms and waited for the silliness to subside.

When the parade passed, the family hiked together behind the remnants of the ancient Leopold Schloss and found a spot in the shade to lay out their picnic.

They spread blankets on the grass and sat down to enjoy the grand repast Mama had prepared the night before. Then, inhaling the exquisite sunshine, Papa and Mama relaxed as the girls performed the play Herma had written to welcome Papa home. Papa stretched out to watch his daughters and, in an unusual display of affection, laid his head in Mama’s lap. She, gentler than usual, rubbed the top of his balding head. When the play was over, the girls insinuated themselves into the mellow moment by resting their heads close to their parents. Sated and spent, they all sprawled on the blanket and slept.

Mama woke first and was in such a mellow mood, she spontaneously began to hum a tune from “Die Schöne Müllerin,” which had been running through her head. Her music woke the others, and it was Charlotte who first noticed lights bursting from the city stretched out beneath their mountain perch.

“Look, Mama, how beautiful! Is that fire? Papa, it looks like the sun is exploding!”

Her parents didn’t share her enthusiasm.

“That could be our house going up in flames,” Papa snapped. His burst of anger silenced the children, who stood transfixed, watching Vienna burn.

Mama feared that they had overstayed their time on the mountain. It would soon be dark, and in the dark, the woods could become treacherous. “Let’s go,” she instructed.

“Mama,” Herma cried, “Is it safe to go home when there is fire all around?”

Mama shrugged.

“Walk carefully,” she instructed. “But quickly. “

Mechanically, they obeyed, racing the descending summer night.

At the bottom of the park, they waited for a bus until a passer-by yelled to them, “Haven’t you heard there’s a revolution in town? No more buses today!”

A revolution!

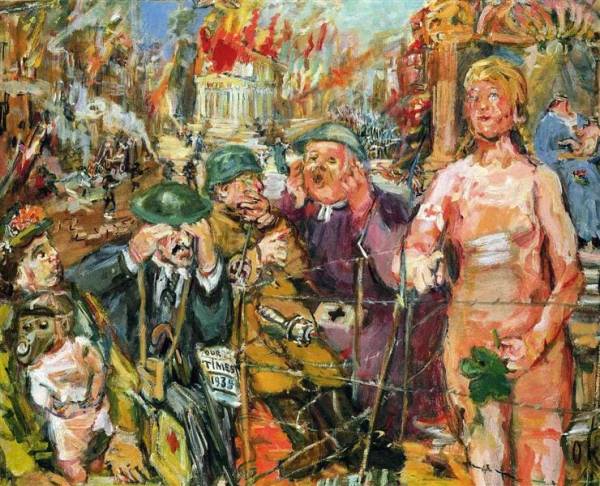

It had begun as a protest strike. In January of that year, in a remote border village, a group of socialists clashed with fascists over the Kaiser’s militarization policy. In the melee that ensued, a barman and his two sons shot and killed a worker and an eight-year-old child. At his trial on July 14, the barman pled guilty but he was acquitted. On July 15, the socialists rioted in front of the Parliament House in the Ringstrasse Plaza. Mounted police, the nationalist Heimwehr Militia, and coworkers brandished weapons of all kinds. Long after the police were ordered to cease firing, the shooting continued. Miraculously, though the fire brigade was unable to get through the barricaded streets, the fire remained contained in the one building, and by morning, the revolt was over. Six hundred people were severely injured, 89 were killed, and the Palace of Justice was demolished.

In the ensuing days, reports in various publications blamed the uprising on the Jews, who, because of their Eastern European roots, were said to be Communist agitators.

As the conflagration raged, the Robinsons knew only that they needed to be home. No public transport was running, but they found a taxi with a driver who thought they looked like refugees. He drove cautiously through the fire zone as the family huddled close to the floor of the cab, seeking cover from the gunfire that echoed through the normally hushed streets now teeming with confusion and terror.

At the Ringstrasse, soldiers stopped them with hoisted bayonets but altered their stance at seeing Ruth’s bandages. One of the soldiers said, ‘That little girl’s been hit. Let ‘em pass. She’ll need medical attention.” No one contradicted the soldier’s surmise.

The family’s home was unaffected by the fray. No fires, no guns, no screaming citizens. Henri drew the shutters, barricaded the doors, turned off the lights, and took the children into the master bedroom, where they all spent the night.

The frightening events stayed far from their inner sanctum, where the sisters were protected and loved. For them, the day was a glorious adventure marked by an outpouring of parental affection. By their own recounting, all three were too excited to sleep yet too afraid of their parents to get up, so they lay awake holding hands and listening to the night. In the distance, they could make out sounds – the toy-like popping of guns, wailing of racing water trucks, clomping of running boots – like background sounds in a radio play. Eventually, they must have slept because suddenly it was over, and their little corner of the morning sun-drenched city glistened as though nothing had happened.

The city had gone quiet. A general workers’ strike persisted for a few days, but there was no more violence. Except for the charred carcass of the Palace of Justice, all evidence of Friday’s melée seemed to have faded.

Later in the week, returning from a piano lesson, Herma brandished a leaflet being handed out on the street. “This is about the riot,” she reported. “They’re saying it was just a demonstration. A blowup by the Communist workers. The Heimwehr militia was doing its job, protecting the city.”

“Fascists,” Papa muttered.

“They’re saying the Communists are taking over the country. They plan to make puppets of us all.”

Papa scowled. “If they’re saying Communists,” he said, “We better start packing our bags. ‘Communists’ is just another word for Jews.”