The world has lost a source of light this week. My friend Eleanor Sweeney has left the planet, and with her goes the last non-family link to my mother, a link that gave me permission to see my other as the whole woman she was.

Eleanor and my mother Charlotte became friends the year my baby brother John began Kindergarten, the end of 1966. In those days, it was a rare Kindergartner’s mother who was nearing 50, which my mother was, and she felt out of place.

“I feel like I did when I was working as an RA at UVM,” she told me that October. “I’m the experienced older woman, and they all look to me for wisdom, and I can’t admit that I’m still just flailing like everyone else.”

Eleanor made her feel normal. Their fourteen-year age difference was never uncomfortable for either of them.

They met through their sons. Within weeks of beginning school, John and Eleanor’s oldest boy were best friends, and they began visiting one another’s homes. Mom and Eleanor began to talk. It was easy to talk with Eleanor. She listened intently and answered astutely. They began to share details of their lives as mothers of multiple, active children. Eleanor had three small boys; Mom had three girls and three boys, ranging in age from 6-14, still at home. I had left for college in September.

Before Eleanor entered the picture, I remember mom going to College Club and PTA meetings, but she did not socialize with her cohorts or get close to anyone in particular. With Eleanor, friendship quickly blossomed into a personal attachment. They talked on the phone, commiserated about kids and husbands, shared driving responsibilities, and nurtured a kind of surrogate sisterhood.

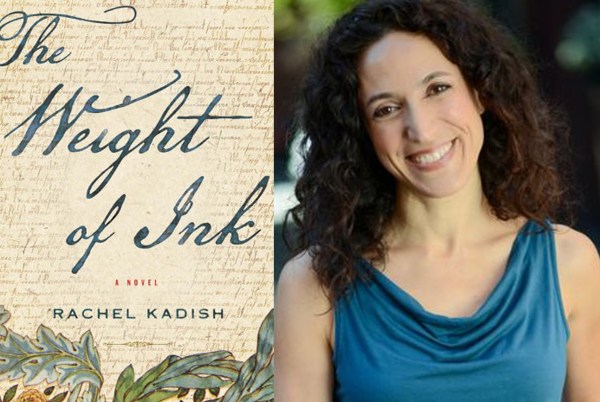

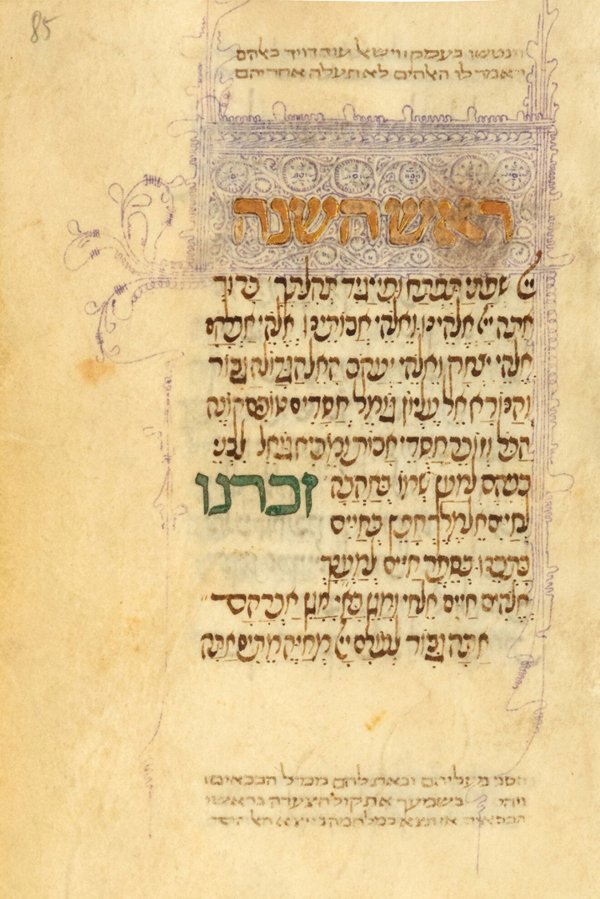

Eleanor was the perfect confidante for my mom, whose European upbringing and old-world sensibilities were often misunderstood. She had been an expert cellist and loved music, was a reader of all manner of literature, and grew up in a house where art was the center of everything. Eleanor was a reader, loved books, music, and culture in general; moreover, Eleanor was an artist, a free-thinking photographer, with a keen eye for what made the natural world seem otherworldly. They were both linguists who could converse about art or literature or current events in English or Russian; each was the center of life in her home and could equally prepare meals, do the laundry, analyze great ideas, and, when necessary, fix minor plumbing issues. They were heroic women.

By the time I got to know Eleanor, I was the mother of grown children, and she was divorced and a grandmother. My mother had told me I should get to know her friend, but I had had little opportunity. I liked her on the few occasions I met her, but we were not friends until the 1990s. My mother died in 1999, and friendship with Eleanor became a kind of imperative for me, a force for which I shall be forever grateful.

Soon after mom’s death, another friend from our hometown sighed, “I wish your mother had been mine. She was perfect.” I could not respond. My mother was certainly anything but perfect for me, and it took time for me to learn how to love her appropriately. Before I could articulate any of that, Eleanor spoke up. “Charlotte made me appreciate my mother precisely because she showed me how to love an IMperfect mother.”

What an epiphany, I thought. That is just what Eleanor is doing for me!

Over the next 25 years, we saw each other through a number of life changes. I divorced, her grandchildren grew up, and mine were born; she suffered great losses, and then so did I, though never quite as great. We didn’t talk all the time, but when we did, we connected deeply and spiritually.

Eleanor and my mother taught me what an extraordinary gift an intergenerational friendship can be, and I have learned to nurture the same with younger women as I age. I cherish the time I got to spend with Eleanor. I will miss her, but her presence is unextinguishable in my sense of self, my appreciation for life. Perhaps someday a younger friend of mine will feel the same about me.

I doubt Eleanor knew what a giant print she left on my heart. She was far too humble to have sought it out.

Eleanor was one of the founders of the Adirondack Artists Guild; she is pictured here in the Guild’s Gallery in downtown Saranac Lake, NY. The Guild will host a celebration of Eleanor’s life and work in January