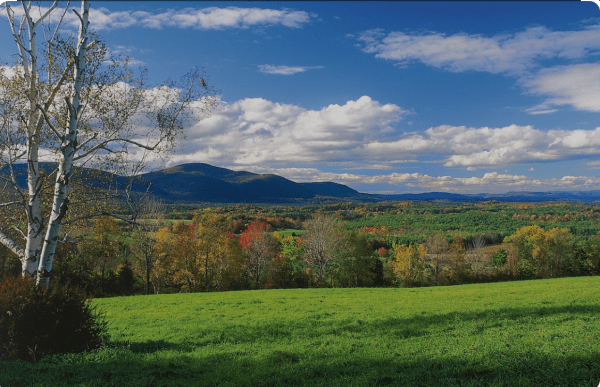

Walking in the almost cool, late August air today, I felt a premonition of Fall. Crisp air, cornflower sky. Finally. . . October’s on its way.

October has always been a special month. My birthday, my youngest child’s birthday, the year’s first cold snap, darkening afternoons. This time, however, the October snippet hit me with an image of Marilyn Joan Alkus Bonomi.

Mari and I met on an October Saturday in 1987 at my youngest’s birthday party, a party I hoped would help us get acquainted with our new neighbors. We had just moved from Arizona to Connecticut, and none of us had been prepared for the culture shock we would encounter. Fitting in was challenging, and a party seemed like an opportunity to make some friends, to show our new cohorts that while we might not have mastered the eastern way of dressing and speaking, we were just plain folks like everyone else. Personally, too, I hoped that an adult or two would come to the party and stay, be a welcoming presence . . . or at least a fellow parent with familiar sensibilities.

Mari was the one. She swept in, deposited her daughter in the midst of the other children, then sat down next to me and opened a conversation that drew me in, made me feel instantly connected. It was a stream of consciousness into which we were able to immerse ourselves every time we were together for the next nearly forty years of our enduring friendship.

We had lots in common. Her daughter and my youngest were the same age and had already begun to bond, which meant that Mari and I were destined to see one another often. We were both English teachers with a deep connection to the theater; she was well established in Connecticut, and I was looking for a job. We shared a nearly obsessive love of rhetoric and a penchant for lost souls. Though humanist Jews, we had both chosen husbands who were Jesuit-trained Catholic schoolboys.

Over the course of that first year, her daughter and mine became besties and formed a union that included my older daughter; Mari and I were fused.

Because of Mari, I quickly found a job. At the birthday party, she had been delighted to learn that I planned to substitute teach while I sought permanent employment. “That is wonderful news,” she said. “I teach at Amity, in Woodbridge, one of the best schools in the country. Can you tell I’m proud? Anyway, we never have enough good subs. I’ll put your name in.”

She did. I spent much of that year subbing at Amity and loving it.

One day, when we were lucky enough to have lunch together, she pointed to a lanky man leaning in among a group of students, listening intently and chatting with them. “See that guy?” She asked. “That’s Stu Elliot. He’s one of our Assistant Principals. A good man. A great administrator. See how he interacts with the kids? He is special, which just means we won’t have him for long. He’ll have his own school any day now. Which is why I want you to meet him. He will want to hire teachers of his own choice, and you would be a perfect addition to any team he takes on.”

We spent ten minutes talking to Stu, and I agreed. He was remarkable. A year later, he became my principal at the high school next door to my house. I could not have been more fortunate, and my gratitude to Mari never diminished.

Our friendship ran deep. Her child was at my house almost as often as mine was at hers. We celebrated holidays together and commiserated when we were both unhappy. Our contact lapsed a bit as each of us traversed the hard road of divorce and redefinition, but we found one another again in time to have a few great years as senior citizen sisters. Though never enough time to fully share our appreciation for years of a deeper-than-blood kinship.

Since 1987, my life has been fuller in dozens of ways because of Marilyn Joan Alkus Bonomi. Though she will live on in her daughter’s eyes, in her grandson’s laugh, in my heart, in my soul, in my very vivid memory, I shall miss her voice, her presence, the soft touch of her abiding love.