What I remember most about being young is how much older I was then than I am now. There was a supercilious seriousness about me then, a clarity I could never recapture.

My best friend in the 1960’s was Northern Calloway, who resided with his family in Harlem as I did with mine in Queens, but we spent most of our time with theater friends in the Village, where we felt the safest. Mixed race friendships were less unusual in the Village then than in Harlem or in Queens.

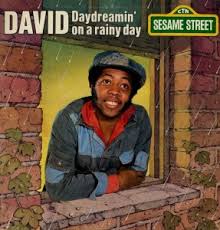

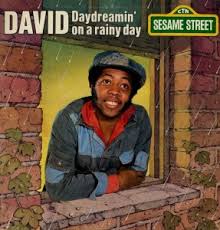

You might recognize Northern. He was in the original Sesame Street cast, as Mr. Hooper’s assistant David, and he understudied Ben Vereen as the Leading Player in Pippin before he took the role to London. Three months younger than I, Northern had absolute certainty that he was right. Always. About everything.

“You and I might love each other now,” he’d tell me. “But you know some day, we may have to take sides.” We had heard Malcolm X speak just months before the assassination, and he insisted that I regard X with the same reverence he had for the man.

“You and I might love each other now,” he’d tell me. “But you know some day, we may have to take sides.” We had heard Malcolm X speak just months before the assassination, and he insisted that I regard X with the same reverence he had for the man.

“He’s a beautiful speaker,” I told Northern. “And I admire his courage. But it’s not that black and white. Dr. King –“

Northern was exasperated when I spoke of MLK. “Dr. King’s a delusion,” he’d proclaim with all his youthful self-righteousness. “And you’ve chosen exactly the right words. It’s ALL about black and white. King makes it seem like you and I could wind up on the same side in a race war, but Malcolm tells it like it is. There’s y’all and there’s us, and someday I might have to side against you. I might even have to kill you.”

The notion terrified me. The year before a kid named James Powell had been shot by an off-duty policeman, and all-out riots erupted first in Harlem and then in Bed-Stuy. Before long, the terror spread as far from the city as Rochester, and Governor Rockefeller called out the National Guard. I had seen the ugliness of the mobs, had felt the hatred on both sides, and I did not want to have to choose one or the other. In my estimation, there was right and wrong on both sides, and I envisioned a world in which each side could find ways to appease the other, agree on compromises.

“You be fool,” Northern told me then, lapsing into his very cultured version of street lingo. “But it ain’t your fault. You not Black. I ain’t white. We ain’t never gon’ see things the same. You cannot know what my life is like.”

Of course I disagreed, and I was certain he was wrong. I was an actor, a writer; I had a reputation for being overly empathic. Besides, even though he lived in Harlem, he wasn’t really from that culture either. Raised by his Cambridge-educated Jamaican grandfather and his school teacher mother, Northern’s background seemed closer to my own jumble of immigrant cultures than to those of the people I saw when I visited him. It never occurred to me at age 15 that he meant he was Black, and I was White, and that was that. I had a penchant for overlooking the obvious.

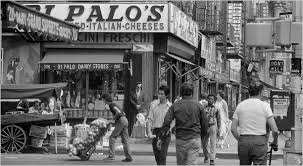

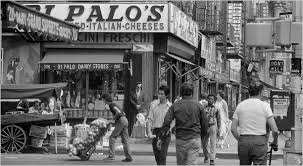

But I couldn’t ignore it forever. In 1966, I needed to move from Queens to Manhattan, and one day I found a listing in the Village Voice for a place I knew I just had to see. “Dig it,” I told Northern. “It’s, like, a studio. On the ground floor. It’s got a garden. A hundred a month.” “Where?” Northern inquired. “Houston Street, just east of Elizabeth.” Northern was audibly indignant. “You kidding me? That’s Little Italy. You wanna live there where all the racists live?” I refused to believe him and convinced him to go with me to look.

The apartment was everything the ad suggested it could be. Sunny, clean, newly renovated. The landlord told me that he paid his dues so no one messed with him. I had no idea what that meant, but I wanted to live there. Again Northern scoffed. “You wanna live with the Mob? You think so? You gon’ be sorry, girl!”

I was devastated when the landlord called me to say that while I seemed like a nice kid to him, he couldn’t be so sure about my friends if they were all like the thug who was with me when I looked.

A thug? Northern? Whose clipped, almost British accent made this landlord sound like a caricature of the dumb wop? I wanted to argue, but I was too flabbergasted to say anything. Instead I hung up the phone and dialed Northern. “I told you you was trippin’,” he laughed. “Niggers are not welcome in Little Italy. You should ’a’ listened to me in the first place.”

I hated when he was right.

Northern hated cops. I didn’t. I had had two experiences with New York cops that made me love them. The first was when my friend Norma, a single mom, eking out her existence working with me as a proofreader in a management counseling firm, returned home with her 10-yr-old daughter one night to find their apartment had been ransacked. Norma didn’t own anything worth stealing, but her daughter owned a jar of coins –quarters, dimes and nickels she’d been saving for eight of her ten years– which was the only item taken from the apartment. The investigating officer felt terrible for the little girl and asked her how much she had saved. “I dunno,” she replied. “The last time I counted, I had 47 dollars and 27 cents. That was a few weeks ago.” The man reached into his pocket and handed the little girl a wad of bills. “Put these away,” he said, patting her head. “And don’t be spendin’ it till Christmas.”

Northern spat on the ground as I relayed the story while we crossed through Rockefeller Center. “And you think that proves they’re nice guys?” I said all it proved was that all cops were not pigs. “Well,” he scoffed. “If she weren’t white, I bet the outcome would‘ve been very different.” I ignored him.

The second time a cop actually saved me from myself.

In those days there was a popular product called Cupid’s Quiver, a scented, flavored douche that was sold in sets of twelve small plastic vials packed neatly into a rectangular acrylic box, the perfect place to keep a stash. Perfectly rolled doobies nestled comfortably into the spaces intended for the vials.

One fine Saturday night, making a delivery for my dealer cousin to the Village, I fell in the subway station. My purse opened to spew forth its contents, including a Quiver. Twelve charming marijuana joints tumbled onto the concrete floor. In a panic, I scrambled to scoop them back into their little pink box, when suddenly, crouching next to me was a NYC Transit cop. Visions of rock piles and leg chains danced in my head, and I could hear strains of NobodyknowsthetroubleIseen playing behind my eyes, when the cop handed me four joints he’d already collected. “Lemme help you with these, little lady,” he crooned. Ordinarily, I allowed no one to talk to me like that, but under the circumstances I held my tongue.

“Yeah,” snapped Northern when I told him about the incident. “May I remind you that you ain’t no black man?” This time I knew he was right, and I thanked my lucky stars.

In the end, Northern and I parted company over a difference in perception that had nothing to do with race but had everything to do with how driven we were by the politics of our generation.

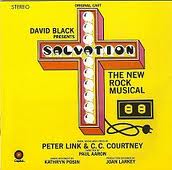

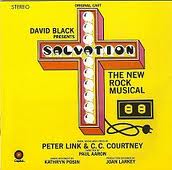

In 1969, Northern was headlining in an off- Broadway play called Salvation, an anti-war musical, about a Baptist kid who becomes a guru for the under-30’s crowd, delivering a messianic message à la Timothy Leary. That was the same year I went back to school at Columbia, and a very close friend of mine from high school, deployed to Vietnam, stopped in to see me on his way to Saigon.

My friend and I both wanted to see Salvation, and when I asked Northern if he could get comps, he arranged for producers’ seats, the best in the house. There was one hitch: my friend had brought nothing to wear but his uniforms. We were conspicuous in that audience, to say the least.

During the show, whenever the politics got hot on stage, some cast member would point to my friend sitting next to me and make ever-worsening references to the “buzz-head blondie” in the third row. I was ashamed – not of my friend but of the cast. How dare they judge him and stick him out for his choice when he was there to celebrate their choices?

After the show, Northern sent word that he couldn’t have dinner with us as planned. I got the message loud and clear, and I didn’t see him for a month. He didn’t call me, and I didn’t call him. Then one day I was walking near the fountain in Washington Square Park when I heard my name. The voice was unmistakable.

“Hi, Northern.”

“Hi yourself, white girl.” We hugged, kissed, held each other for far longer than a simple hello would warrant. Then we just stood there, looking at each other, holding hands, not having anything to say.

“I’m thinking it’s time to forgive you,” he said finally.

“You? Forgive me?”

“Yeah. For bringing that fascist Clyde to the show.” Fascist Clyde meant stupid storm trooper.

“You don’t know anything about him, and you –“

“ He was wearing a war machine uniform. Where’s your Lysistrata passion?”

“He knows how I feel, I don’t sleep with him, and he has the right to maintain his own point of view. It’s not up to me to legislate beliefs for any of my friends.”

Northern squeezed his eyebrows together, and he nodded ponderously. Then he shrugged and pulled his jacket lapels up around his neck. “Well, I guess that’s where we are different,” he said. “I do.”

He turned and walked away, and that was the last time I ever saw Northern Jesse James Calloway. Years later, as suburban teacher, I was on a bus crossing through Harlem en route from Connecticut to the Asia Society, when a scrap of newspaper hit the bus windshield. The driver got out and brought the offending piece of paper, a page from the Daily News, inside. For some reason, I turned the page over, and there, in black and white, the headline read, “Actor Northern Calloway Dead at 41.”

It was a bizarre moment, like the result of divine intervention, too surreal to have happened. But it did.

I think about Northern a lot lately. I’m the one living in Harlem now. But like the old adage says, “The more things change –“

The other day I was on a bus, headed downtown, and I happened to eavesdrop on a conversation between a young Asian man and a tall, African-American woman. They were arguing about the Eric Garner decision.

“It’s complicated,” he said. “There’s so much we don’t know.”

“Yeah,” she agreed. “And there’s too much we do know. The cops just –“

“I dunno,” the young man argued. “I don’t think it’s so clearly black and white.”

“That’s exactly what it is,” said the girl, laughing a little. “Simply put, there’s y’all and there’s us, and someday I’m gonna have to take a side.”

I could swear I heard her say then, “I may even have to kill you.”

Share this and follow me; I'll follow you!

It’s an old motel that should have been sold years ago. But since there are no plans to develop the town and entice investors, no buyers offer deliverance to the owners; they keep struggling along, falling behind on mortgage payments in the off-months and barely making it up in the tourist seasons.

It’s an old motel that should have been sold years ago. But since there are no plans to develop the town and entice investors, no buyers offer deliverance to the owners; they keep struggling along, falling behind on mortgage payments in the off-months and barely making it up in the tourist seasons.