Variations on a Surreal Scene of Violence

Show me the country, where the bombs had to fall

Show me the ruins of the buildings, once so tall

And I’ll show you a young land

With so many reasons why

And there but for fortune go you and I, you and I.

Phil Ochs

1. This is personal

I am a first generation American Jew. I am here by a fluke, by the accident of my mother’s survival, the miracle that she was not exterminated by the complacency, conciliation and paralysis that killed 6 million of her co-religionists and at least 5 million of her co-Europeans over a period of less than six years.

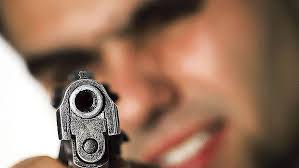

As the child of that happenstance, I owe a huge debt to my grandchildren. It is absolutely necessary that I not keep my mouth shut, that I not stand by and watch as Rome burns, that I not look the other way when society and government conspire to allow rampant murder to take over the country. It is time I look you in the eye and say aloud that if we do not find a way to stop mass murderers from infiltrating our schools and theaters and shopping centers and lives, each of us is complicit in the deaths and/or maiming of every victim.

All right. I’ve spoken. I’m probably preaching to the choir. Our voices join in outrage.

Now what?

Trouble is – and I’ll bet this is what happened to a lot of folks who might have wanted to change things in the 1920’s, 30’s and ‘40’s – I don’t know what we should DO. I have a perseverant Facebook friend who posts every few days that she may be only one voice, but she will keep saying how terrible it is that kids die in places like Newtown. But a voice, a post on FB, is not enough. What action can we take?

Well, to begin with, we might attempt to take down the gun lobby, get them to back off their insane stance that assault weaponry belongs in American homes, that armaments equal liberty. There is no question that the idiocy that prevails over our legislative bodies needs to be tempered with something like intelligence. It would be a good place to start, but we all know that even controlled guns, like controlled substances, can be lethal. The weaponry used in the Newtown slaughter was duly registered to the mother of the assassin. Further, in Canada where guns stand at the ready in every corner, there are no mass murders akin to ours.

Clearly, gun laws are not The Cure. Yes, we need stronger enforcement of more stringent laws, but the American black market is a cornucopia of easily obtained ill-gotten gains; gun laws won’t stop the killings. What else?

We need better health insurance and a medical community equipped to fully treat mental illness rather than stuffing sufferers with pills and telling them to call in the morning once every six months. We require a national societal outlook that accepts that mental disorders are as honorable as any other; no one hides diabetes in the family closet, but few are willing to talk openly about the schizophrenic who lives upstairs. That has to change.

We need more empowered and more effective training for law enforcers. When the Isla Vista murderer was reported to local police for his stash of weaponry and his menacing, disturbing videos, the police found him “polite” and “well-mannered” so they left him to his diabolical planning. That boy’s red flags were waving all over the Internet, all over his lifestyle, all over his face, and no one took him seriously because he was polite and well mannered? Who trained those investigators?

We need sensitivity to the vagaries of iconoclasm. Perhaps rather than labeling some of the perpetrators, if their communities had found a way to embrace them, they might have facitated ways to work out anxieties and anger. As a drama teacher, I often saw misfits find satisfying niches that turned their outsider statuses to a special kind of belonging, and I know that drama’s sister arts – music, individual sports, crafts, visual arts, etc. – are equally adept at “normalizing” weirdness.

We need mitigation of the violence we call entertainment and/or to understand why mad violence is so compelling to us all. A favorite character on the unremittingly brutal Game of Thrones is stabbed in the eyes, and everyone shudders but no one fails to tune in next time to see who’ll be the next prolific spewer of blood. Life on television and in video games is a bowl of splayed intestines, relentlessly devoid of sanctity. But while video games, television drama and even the news might inure our youngsters to the savagery around them, it is not the reason some carry AKAs into elementary schools and shoot five- and six-year-olds.

I could go on, but the point is clear: there is no one way to stem the tide. And even if every item on the list suddenly appeared in our communal midst, the ill might not be cured.

Because the one thing we need absolutely is a way for all of us who decry the violence to work together. We need organizations that send us out into the communities to preach and teach and listen and learn. We need to host meetings where kids and their parents and the disgruntled and the disenfranchised might come together for group support. We need to create a movement through which we are empowered to act.

A few groups do exist that claim to be fighting the madness, but when I try to get involved, they offer me no action; they simply ask for money. I have none. I can write, and I can speak, and I’m experienced in working with people; I want to put my skills to work making a difference. It should not matter that I am not solvent enough to contribute financially.

I am as baffled by it all as the next one. But other countries with problems far worse than ours, with cultures that have far less aversion to violence than ours, do not suborn the kind of terror we seem to be witnessing with increasing frequency here all over the country. I do not want my legacy to be my silence. I do not want my descendants to judge me complacent.

There must be something we can DO. Now.

What about we start with a mass protest meeting? We all join on Skype or Google or some common space online, and we have a huge symposium to brainstorm solutions. We sign a promise to sling no blame. We vow to listen to all suggestions, make no judgments, and we select volunteers to compile our ideas and to schedule follow-ups until we have plans of action, at which point we set about implementing them.

Anyone have another suggestion? It’s time. While we still have some.

2. Nobody is Safe

I’ve been thinking a lot about my friend May these days. May’s not her name, but everything else I write about her will be faithful to the person I knew.

May and I taught together in a fairly small English department in a mid-sized town in Connecticut. She was a veteran by the time I began teaching, though we were nearly the same age. She is one of those exceptional people called to teaching, and while I did not agree with her approaches, she was undeniably driven to spend her life in a classroom. She loved her work, loved her school, loved her students.

But more than that she loved her family. Her husband was a semi-retired business owner, and together they kept horses, which both enjoyed riding. They had a daughter whose disabilities made her dependent on them for life, but whom May adored with unfettered warmth. But the light of May’s life was her talented, intelligent son.

Because I had a son a few years younger than hers, and because my son was a very accomplished young man who attended our school, May never tired of sharing photos and mementos from her son’s glory days in high school, then college; and when I left my position as a teacher in the room down the hall from May’s, that son was about to be married to a girl May adored. May was beside herself with joy. Grandchildren were on her horizon, and she was thrilled.

I didn’t see May for a lot of years. I left that school, moved to another one and then left teaching altogether; I hardly thought about her. But when Newtown happened, I saw that one of the children murdered there had her last name. Unwilling to imagine the bottomless pain of being a parent of a Newtown parent, I dismissed the name as a coincidence until a week after, when someone I knew from that town wrote me to tell me that the child whose name I had noticed was indeed May’s grandson.

Connecticut is a small town, and May’s was not the only family I knew pummeled by the awful rubble. But having reached grand-motherhood myself, having spent so many hours hearing the golden son stories, the news of May’s loss struck me like a serrated knife slicing away the edges of my heart. I couldn’t even write to her. I hadn’t been in touch with her for over twenty years; it would have seemed to her disingenuous to write of sympathy, of love. I was dumbstruck.

There is no bottom to the kind of despair I envision in the wake of such a loss. And today, for the 75th time since that horrific day in Connecticut, another grandmother’s life has been strangled by a duly registered semiautomatic pistol aimed pointlessly at her child’s child.

It is time to stand up as a nation and say ENOUGH. We will take no more. We will make it stop. And we must do it now. We have no time to lose. We are all being watched through the sights of those guns aimed at our loved ones. Those guns must be hobbled.

Now.

Share this and follow me; I'll follow you!