Summer is my season of Daddy.

Most of the time, he was a restless man, my father, with a permanent expression of perplexity on his face. Relaxation was beyond his ken. He was in constant motion every waking minute of every day. Stress seeped from his pores and put us all on edge. A milk spill could create a firestorm of screamed recriminations. He never used bad language, and yet his anger was obscene.

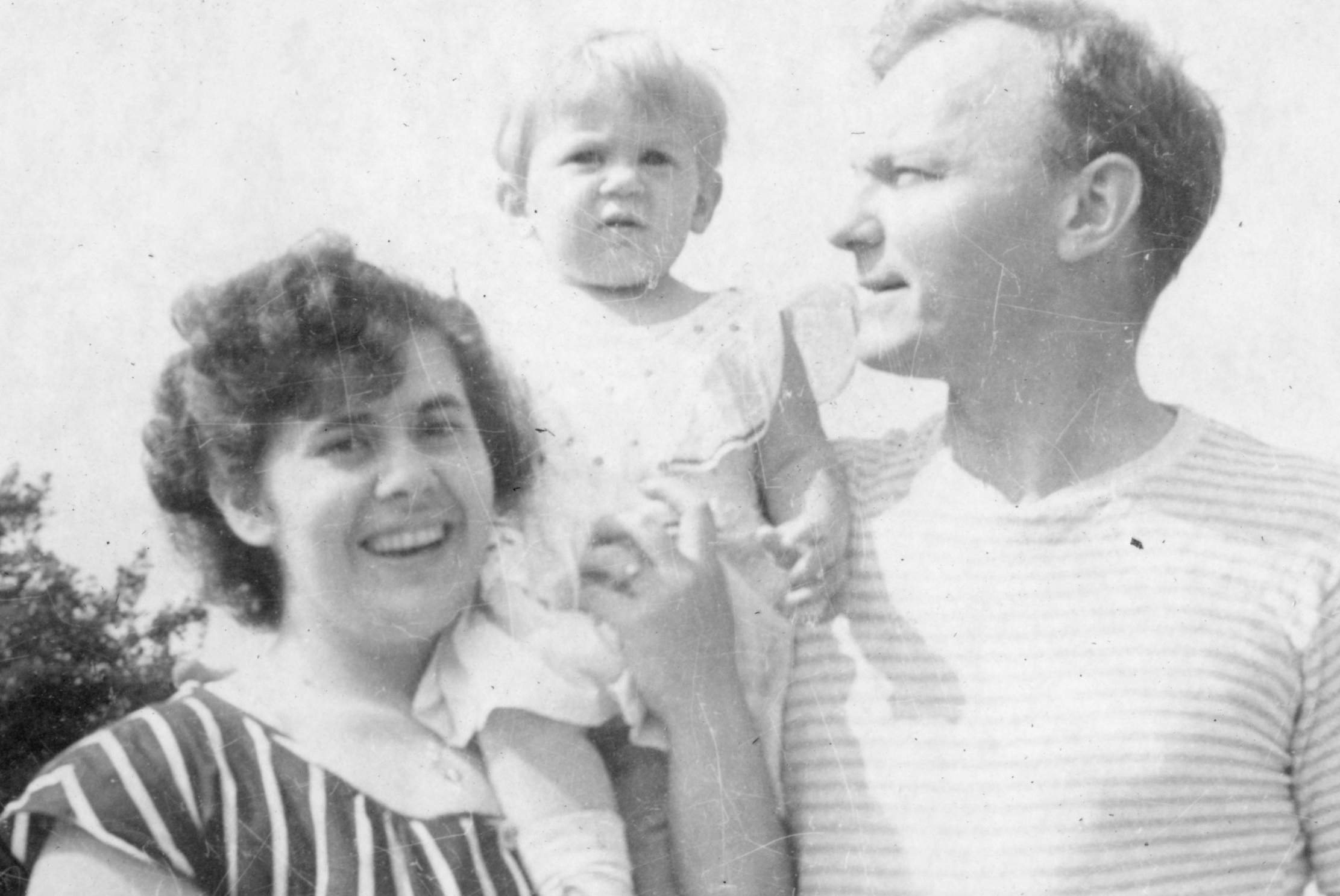

However, on rarified sun-gilded summer days, he was transformed, and I in turn was freed to be myself. At the beach, we could love each other unconditionally.

I attributed his passion for sun and surf to his having been a summer baby. Born the end of July in 1911, in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Father grew up as far from the ocean as an American boy could be. The year he was twelve, right after his father died, he stole the family car and drove it to New York, where his Uncle Milton owned a shipping company. “Let me go to sea,” he pleaded. Uncle Milton summarily sent him home, which only fueled his desire.

Whenever he could sate his thirst for proximity to the ocean, Daddy was a happy man.

Every summer until I was four, we vacationed with my mother’s family in New London, CT. Mom’s older sister Herma was married to Borislav, a Serbian painter of some renown, and he had a patron who loaned him a cottage on the beach, a glorious venue for a family holiday.

My memory of the house – undoubtedly flawed by time and distance — is of a single-story expanse with multiple tall windows standing upright in every room. Their diaphanous, white curtains fluttered and danced in the omnipresent breezes. No matter how hot the air was wherever we had been, the briny, vanilla-scented cool of the beach enveloped us when we entered. Daddy, however, had no interest in the house.

As soon as we arrived and parked our car, my staid, reticent, subdued father would emerge from behind the wheel of the car, shed his grumpy silence, and turn giddy. Suddenly he was playful, happy. He reminded me of those sea creatures we used to order from the bubble gum cards. As soon as we added the salt sea air of the tantalizing water, Daddy would animate. He’d bound into the house, embrace each of the assembled relatives, and rush to any corner that afforded him enough privacy to change into his swim trunks. He could not wait to get into the ocean.

We children – the first three of eleven cousins-to-be – knew what was coming next. “I’m off to the water,” he’d announce. “Who’s with me?”

Cousin Peter, eight years older than I, remained aloof. He was too mature for such childish exuberance. Johnny, eight months younger than I, only went where his mother took him. He would stay behind. I got to have Daddy all to myself.

Stripped down to my crisp white drawers, I would ask my mother to secure my towhead mop into tight braids, and I’d follow him into the gently undulating water. He walked slowly, watching my every move, coaching me to tiptoe carefully over rocks and shells, beckoning me to stop and marvel at the jelly fish and crabs that tickled my shins and scraped my toes. Once, a crab mistook part of my foot for a tasty morsel and chomped down hard. I screamed, more afraid than injured, and my father laughed. “Too bad for that little guy. You’re way too big a prey for him.”

In the afternoons, Daddy, who never rested at home, took a blanket down to the edge of the Sound. He would wrap himself up, put a hat on his head, and coo, “Nothing like the sound of the ocean to sing me to sleep.”

He would nap for what seemed like hours, while Peter, dressed in his cowboy chaps and holster, pointed his toy pistol and chased Johnny and me all about the beach. Our mothers would watch us, laughing and applauding, as though we were brilliant actors in a spellbinding film.

Nowhere else, at no other time were we as insouciant as we were then. Uncle Borislav would join us on our beach blanket when he took a break from his easel, and if there were no Yankee game on the radio, Uncle Fred would be there as well. Borislav performed magic tricks, and Fred told silly jokes. My father, cocooned nearby, smiled in his sleep. We ate dinner on the patio and told silly jokes, then slept with the windows open so the sea could sing us its lullaby.

Daddy would wake me before dawn to watch the tide come in. We would stroll along the waterline, giggling at the horseshoe crabs scuttling away, peering strenuously into the half-light for a glimpse of a ship or a dolphin. We would wade in and let the deepening water lap at our legs.

Whenever the tide was lowest, he would invite me to a grand adventure.

“Come on,” he’d chortle. “Let’s walk to China.”

“No, not China,” I’d laugh. “Paris!”

“Sure! But you have to hold my hand. It’s a very long walk.”

We would splash in, the water level unchanged for what seemed like miles. When we were finally far enough out that I became buoyant, he’d hold me while I half walked, half swam among the sailboats lazing in the summer sunshine.

“Maybe we won’t get all the way to Paris today,” Daddy would sigh at last. “Let’s come back tomorrow.”