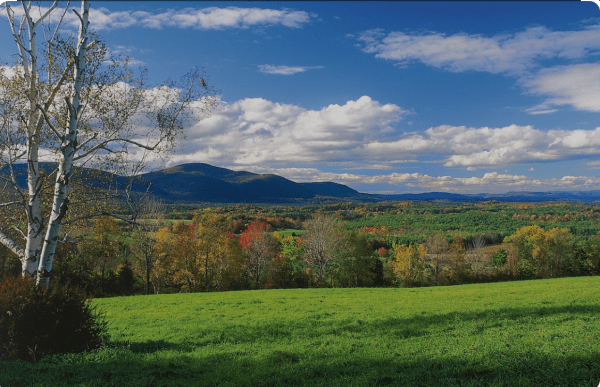

]New Year’s Day 1951. I am 3. Daddy wakes me early. He has dismantled the Christmas tree and tells me we are taking it to the country. . . We’ll leave it with food for the deer in the forest.

“Why can’t we keep it here Daddy?”

“Mommy wants to clean the house. You’ll be big sister soon.

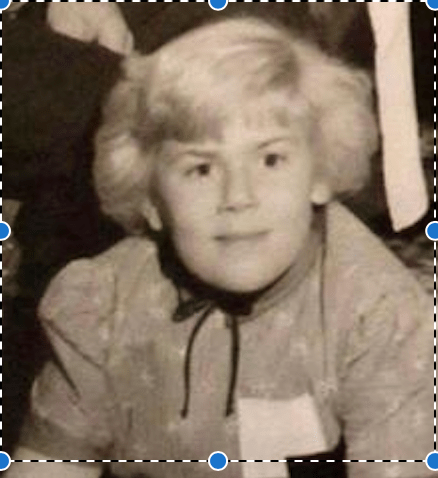

Big sister. Confusing. Dorothy is my big sister. She is 18, a grown-up,. She takes care of me when she comes home from college. I’ll be big?

Later that day, Daddy comes into the apartment carrying a big basket with a hood over one end.

“What’s that?” I ask.

“It’s a bassinet. A bed. For the new baby.”

———————————

I did not understand. What was a “new baby?”

We had no television, and except for my cousin Johnny, who was nearly the same age as I, I had little contact with children. We lived in a basement apartment in a bustling Flushing, Queens, neighborhood, and I am sure there were children all around, but our social life revolved around my mother’s parents and sisters, who, still reeling from their narrow escape from the terrors of Europe, had not begun to venture into the community.

I had dolls. Silent, inert, boring. One drank from a small plastic bottle and expelled water from a hole between its legs. Most uninteresting. If that’s what a baby was, I wanted no part of it.

“Don’t worry,” Dorothy said. “When they bring him home, you’ll love him.”

Perhaps.

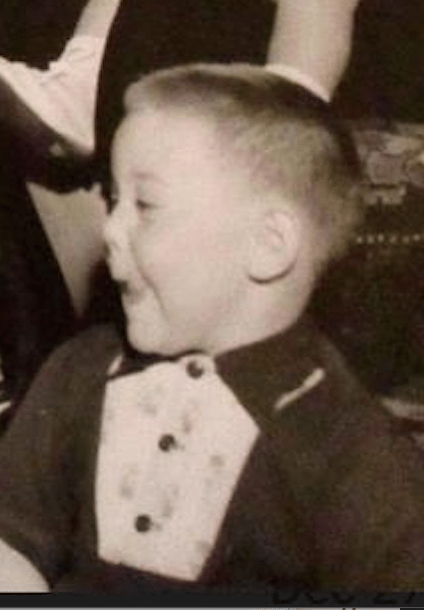

Early in the morning on January 9, Daddy woke me. “You have a baby brother, Carla,” he whispered. “His name is David.”

Baby brother. David.

They brought him home on January 13.

We were sitting in the little living room at the bottom of the entryway when the doorbell rang. Dorothy ran up the stairs to open the door; as the cold wind swept into the room, I saw my grandmother’s imposing silhouette blocking the sunlight, and I heard her muttering something to whatever she held in her arms. Behind her, Daddy cautioned, “Watch your step, Mutti. It could be slippery, and. . . “

As she descended into the apartment, I saw that she held a strange, bundle of squirming blankets, and she was scowling.

“This baby will wiggle out of my arms if I don’t put him down. Sit on the couch, Carla.”

I froze. Why did they want me to sit? Daddy had gone back to the car to get Mommy, and I wanted to see her not sit.

“I said, sit, young woman.” When grandma became authoritative, she was imperious.

I sat.

“Straighten up,” she commanded.

I did.

“Hold out your arms.”

I obeyed.

Then she placed her bundle into my lap.

“This,” Grandma announced, “Is David. David Walter.”

“Oh,” I mumbled, genuinely disappointed. He was a round, red, wrinkly thing. His skin was blotchy, and his eyes, buried in the deep folds of his face, squinted as he began to wail.

“Please take him back,” I begged.” He’s ugly.”

I let him slide off my lap, and Grandma gave me the evil eye as she caught him.

“He is yours, and you will take care of him. From today on, for the rest of your life, this is your little brother.”

She put him back in my lap. Dorothy sat next to me and wrapped her arm around my shoulder. “You’ll see, sweetie,” she whispered. “You’ll grow to love him. The way I learned to love you.”

That soothed me. I trusted Dorothy. I felt her love, pure devotion, and I believed her unconditionally. I understood the concept of being her little sister.

From then on every January was about David. He was often ill, nearly died of bronchitis and developed asthma before his 2nd birthday, but he was never sickly. He was adventurous, excited by every new experience we could share, and even before he could talk, he seemed fearless and was confident that his big sister would be at his side.

David changed my identity, and though he was not the last to call me Big Sister, he was uniquely fused to me as I was to him.

When our sister Helen was born 3 years after David, he and I became the big sibling duo, cleaving tenaciously to a private language, to private rituals of play, to shared secrets that excluded Helen and each of the 5 babies who followed her into our lives. Our parents changed; the soft sweetness of their marriage became increasingly hostile, and their way of dealing with issues became more unrecognizable with each passing year. Helen was young enough to take them as they were, but David and I understood that the parents we knew resided in a pocket of memory to which only we two were privy.

Dorothy and I saw each other infrequently as I grew up – she married a Los Alamos scientist and built her life with him and their six beautiful children in the New Mexico mountains; my parents settled us in the northeast. When we visited on another, Dorothy and I had little to be nostalgic about. She told me stories of her life before I was born, stories of what little she remembered about her own mother, stories that included grandparents, aunts, and cousins whose lives ended long before mine began. She knew little of my childhood, as she was in college, then in motherhood before I started school. She existed in a universe I could never see except through her singularly focused lens, and she had less and less time to know mine. We cherished one another, but we had little commonality.

David’s and my pasts intersected and connected; we existed in the same time and space.

Over the years of marriages, divorces, and remarriages, births of children, parenthood, and grandchildren, we weathered the storms and celebrated the joys in tandem. We would butt heads, and we might lose touch from time to time. But we always reinvigorated the bond, reinstated the closeness that was buoyed by our collective memories. If we felt wronged, we always forgave, always valued the revival of the relationship.

The other kids, whose births came in quick succession after Helen’s, established their own private bonds, which omitted us just as we had omitted them. I am now aware that there were things I didn’t know about that perhaps I should have seen, but I left home before David got to high school, and I was caught up in the maze of my own delayed adolescent awakenings. More than anything, we were terribly inept, quasi-parental units, not siblings to them. I was Big Sister to David alone.

Big Sister. Little Brother.

Grandma promised for the rest of my life. She could not have known.

In 1964, when David was 13, he was diagnosed with diabetes, which re-routed his trajectory. The illness cheated David in all manner of ways, and likewise, he cheated death with multiple tricks for as long as he could. After endless surgeries – two kidney transplants, two amputations, quintuple bypass – and seemingly infinite catastrophic illnesses like pneumonia and sepsis, David died in 2023, at age 72.

Now, nearly three years later, I am still grappling with my identity.

So long as David existed, I was a Big Sister. That role helped define my sense of self as a parent, as a teacher, as a human being. I was flawed, but I was tethered.

All but one of our younger siblings have rejected me. I am a mother and a grandmother, who has succeeded in many ways and failed in more. I am who I am. But I am no longer a big sister.

Only David would understand what I mean.