Audio podcasts are a wonderful innovation, especially for those of us with insomnia. Nothing is more soothing for me than a gentle voice talking about interesting worlds. I especially love science, history, and theater talk, film history podcasts, or literary discussions, and David Remnick. It is comforting to feel myself relaxed out of anxiety into someone else’s knowledge and then to drift off to sleep.

I confess that there are many podcasts that irritate me. The ones that make me sit up, desiring to scream into my device– though that is certainly not an option for a considerate apartment dweller in the middle of the night – those that frustrate me with their pontification or false modesty, political rants or misinformation.

The ones that most irritate me are the podcasts that pretend to offer hope and life modeling to women over 50. On podcasts such as unPaused, with Marie Claire Haver, or Wiser than Me with Julia Louis-Dreyfus. These offer advice from the megastars like Isabella Rosselini, Nancy Pelosi, Gloria Steinham, Michele Obama, Jane Fonda, et high-falutin al.

Inevitably, these admittedly wonderful, rightfully revered role models are women who have achieved great fame and fortune. They are most certainly noteworthy, and I deeply admire them and their accomplishments. But they are women who have been receiving attention for a long time already and are rarely in positions to which any of us groundlings can reasonably aspire.

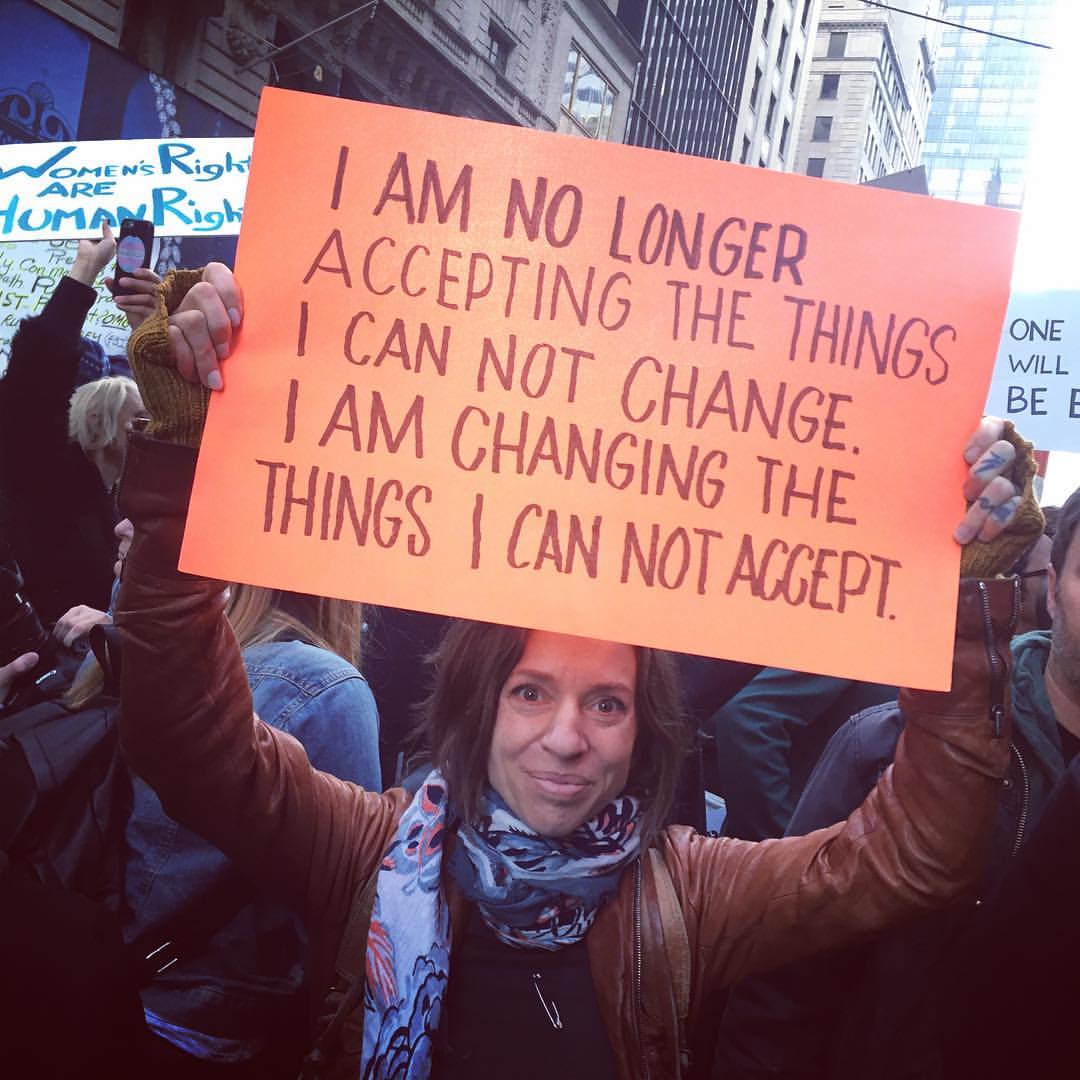

All the while, everyday women who achieve less than phenomenal but still noteworthy successes are overlooked. Despite the fact that we, too, are pundits. We, too, offer stories that could be truly inspirational.

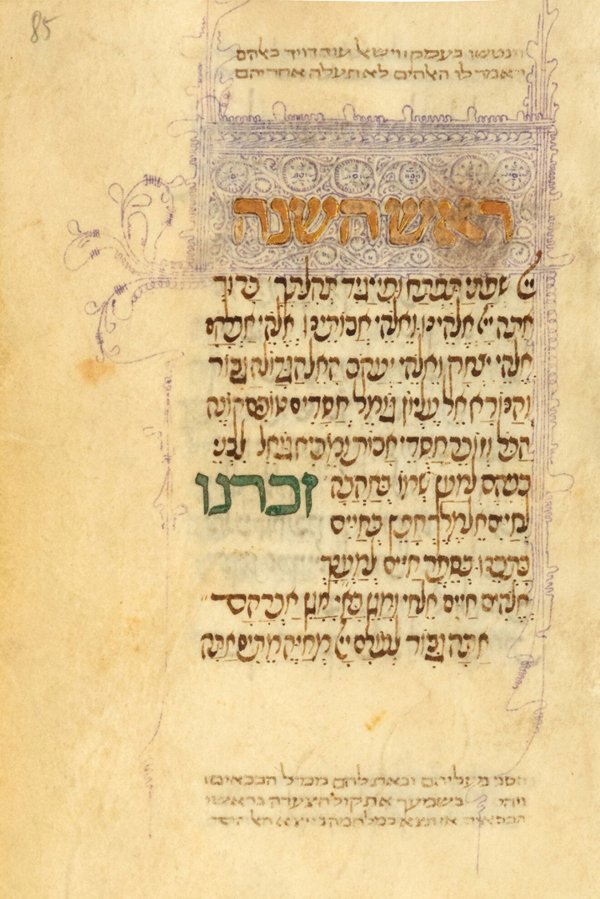

I have many friends who have lived lives worth sharing. Women – mothers and wives — who have written books that may not have been bestsellers but still had audiences and made a difference for their readers. For example, my dear friend, who nursed her husband through harrowing bouts of PTSD, raised her family, took care of her brothers, ran a lovely small business, and managed to paint some lovely watercolors? She knows about survival and rising above adversity and setting goals, and attaining happiness. Another brave woman I know writes songs that aim to forge peace and understanding while curating a huge cache of legacy art, and another creates phonics videos to promote literacy among disadvantaged children. They love their work, and they are proud of what they do, as many everyday women do. Some nurture student artists — those who may not be the Oscar or book award winners spewing gratitude for their mentors — and help them to nurture dreams that lead to meaningful careers that improve the world in multiple ways, Even while schlepping personal children from pillar to post, attending extracurricular activities, keeping husband’s clothes cleaned and pressed, etc., myriad ordinary heroines persevere. Women who work as nurses, physicians’ assistants. dental hygienists, bus drivers, etc., while providing care for elderly parents. Those who act in plays on, off, and way off Broadway, direct educational and community theaters, sing in and direct choirs, play music, and lead small-town orchestras.

You can see my point, I am sure. The accomplishments of women are incalculable.

Surely the multitude of women who have built modest successes are no less interesting than those who have made millions? Is it not exemplary that real people keep plugging away, writing, painting, acting, teaching, serving the sick, and providing goods and services? Aren’t the common variety supermoms/daughters/aunts/sisters/grands apt role models for younger generations?

Come on, social influencers, podcasters, you who want to inspire women, find those of us who fuel the world with its real power. Look for our books, our drawings, our songs, our stories. Ask us what we know. Let us show you how fascinating we can be.