While I refuse to qualify the bizarre allegations levied by misogynistic fear mongerers against Planned Parenthood, I feel a need to make a small statement of support for an institution that I believe in, an institution our society cannot afford to lose.

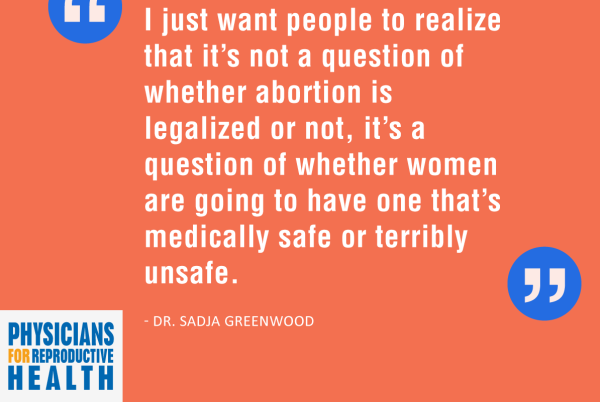

First of all, I would like to go on record by saying that there is no reason for apologia where abortion services are concerned. Abortion is legal in this country, and women have the legal right to choose whether their bodies may be receptacles of new life. I don’t know anyone who is pro-abortion; I am not. But I am pro-choice, including the difficult choice to terminate a pregnancy. Choice deserves and requires protection.

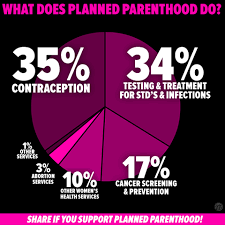

What the critics chronically forget to mention is that Planned Parenthood does so much more than counsel women regarding their unwanted pregnancies. They saves the lives of mothers and children. Planned Parenthood is a safe haven the community cannot do without.

I don’t know anyone who loves going to the doctor for gynecological examinations, but all women need to do so in order to protect themselves against illnesses that attack the female organs. And having access to affordable care and to prevention and cure of feminine illnesses also deserves and requires protection.

Planned Parenthood provides choices, care and prevention that no other institution offers, preserving women’s lives in a variety of ways, and we must stand up for the good that they do lest it be lost in a hale of ignorance and misconception. All pun intended.

- Judy’s Story – Perilous Days Before Roe v. Wade

I was 18 when I met Judy. We were both employed by a large firm in New York whose specialty was writing employment manuals for employers. I was a proofreader; Judy was a typist, and she was 19, mere months away from reaching twenty.

Judy was ever so much more mature than I was in ways I never imagined myself becoming, and she intrigued me. I still lived in my aunt and uncle’s house, where no matter what, I was sheltered, fed, protected from the world. Judy lived on her own in a one-bedroom apartment in Bay Ridge, where she had to cover the rent, heat, food and clothing for herself and her 4-year-old daughter. On my meager salary, I had a hard time keeping up with the minimal contribution I made to household expenses and found it challenging to buy enough clothing often enough to get to work looking respectable. Judy made less than I did, and in addition to all her other expenses, she had to pay for whatever day care her friends were unable to provide.

Hoping always to find a man who would step up where her deadbeat ex-husband had failed her, Judy dated fairly frequently, and I was her go-to evening babysitter. I loved the solitude of being in her house after her daughter went to sleep; I marveled at her house, so clean, so bright and cheerful. She had curtains on the windows, rugs on the floor, pictures on the wall; her daughter’s bed was a frilly pink wonderland. How did she do it?

I loved Judy’s child, who was smart, funny, talented and spirited. We watched Sesame Street together in its first year, and I took her to meet my friend Northern, who played one of her favorite “real people” characters on the show. I was part of the family, intimately tied to them by an interdependence that suited us all.

Judy could not possibly hope to sustain any more of a burden than she was already managing. She often said to me, “Carla, I gotta be real careful, ya know? I mean I got knocked up the first time because I wasn’t payin’ close enough attention. I cannot afford to have another kid.”

But no matter how careful you were in the 60s, pregnancy was never altogether preventable. After seeing a prospective stepfather for several months, she stayed overnight with him, and despite her protestations that she took EVERY precaution, she became pregnant. In those days, many of my friends and relatives were victims of missed pills, defective condoms, miscalculated dates; Judy’s mishap was no surprise.

“I’m a good mother,” she moaned to me the day she got her test results. “I am. But dammit, Carla, what ’m I supposed to do? I got dreams for my kid. I want her to have a good education, do more with her life than I did. I can’t afford another one.”

I had no words of wisdom. There were no alternatives. The would-be stepfather dropped out of sight as soon as he became a prospective dad. Should the fetus in Judy’s belly grow to childhood, it faced a life of poverty that would also drag its older sister into an abyss, an underfed, underserved existence. Judy was despondent.

Then, for a time, we only saw each other at work . I don’t know how many nights she stewed without confiding her thoughts. But one night after midnight, my phone rang, and it was Judy; she was crying and sounded wrung out. “Carla. I need you to get here right away. Please.”

I lived in Bayside, Queens, a long way from Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. I took a bus to Flushing, where I got a subway to a transfer point in Manhattan and then, following Judy’s instructions, emerged somewhere in Brooklyn, where I hailed a cab. She was waiting for me with Norma, a co-worker with whom we often socialized, a slightly older woman who had brought with her her own 8-year-old daughter. I had been summoned to babysit. They left the minute I got there without explanation, but I knew something was terribly wrong.

Judy had no color in her face and could barely move. Norma had to carry Judy down the stairs, and I watched out the window as she lifted my nearly lifeless friend into the cab. I took both little girls with me to Judy’s bed, and we slept through the night. It was after noon before Norma returned. The girls and I were having breakfast.

“She’s going to be okay,” was all Norma told me. When the children moved closer to the television and engrossed themselves in Days of Our Lives, she explained.

“We decided not to tell you last night. If we got arrested, we wanted you to be clean so you could take care of the girls.”

Judy had had her pregnancy terminated by a local “Gypsy” woman. She nearly bled to death, willing to die rather than bring another child into the world. She was prepared to sacrifice her life rather than throw her daughter’s future away.

I was grateful she got away with it. Still am, as I am certain both she and her daughter are as well. That daughter is a prominent physician today.

- Sally’s Tale – In Need of A Safety Net

Sally works overseas, only gets to come back to the States once a year. In the country where she lives, she gets inexpensive insurance coverage that ensures that she has unlimited access to comprehensive health care. Whenever she visits home, she cites the high cost of health care as one reason she feels compelled to remain abroad.

Sally is nearing forty, and though her latest love affair, which lasted two years, ended in a break-up, she was delighted to learn that she was pregnant. Professionally secure and ensconced in a comfortable community in her adopted land, she was sure she could manage the challenge of single motherhood. After a visit to her local physician, who did an ultra sound, Sally left for her annual visit stateside confident that she was carrying a healthy fetus. She could not wait to share the news with her family.

By the time she left for her trip, Sally was feeling uneasy. There had been movement in her womb, but all movement had stopped. Since there were no other signs of trouble, however, she carried on with her plans and made her yearly pilgrimmage. But the discomfiture persisted, so she decided it would be a good idea to check in with an American doctor at an American hospital to make sure all was well.

A family friend, a physician himself, recommended a colleague who worked in a highly respected medical group, where fees would be less than exorbitant.

The news was devastating: the pregnancy had self-terminated. But before the gynocologist had confirmed that fact, he took blood tests and performed the sonogram, which cost Sally upwards of $1200. The doctor told Sally to come back for a D & C, but the costs were so astronomical that Sally was determined to let the miscarriage expel itself naturally over time, a choice, which, as anyone who has been there will tell you, was less than wise.

Over the next several days, Sally’s pain grew, and a deep despondency settled in. She had wanted to bear a child, and carrying this failed fetus exacerbated her physical pain. Finally, seeking advice online and a possible support group to join, she found Planned Parenthood.

Sally conferred with a lifelong friend, who had been without health insurance for many years. The friend confirmed that Planned Parenthood, the only place she could get low-cost or no-cost cancer screenings and overall checkups, was a good choice. Sally made an appointment, and a day later, a kind nurse gently ushered Sally into a comfortable place where a coterie of empathetic women tended to her, prepared her, comforted her as she endured the actual procedure.

The entire experience cost her less than $300.

No other institution in this country offered Sally so much life-affirming concern or treated her with such respect. And no one offered the service at a cost that was nearly as affordable.