When Dan Alon approached me to write the harrowing tale of his freakishly miraculous escape from the Munich Massacre, I was drawn to the tale for its depiction of the process of survival. I had grown up in a family of traumatized escapees from disaster and holocaust, and none of them ever found the vehicle that could deliver them from their ghosts. I was honored to offer my services to help build the transport for Dan’s journey.

When Dan Alon approached me to write the harrowing tale of his freakishly miraculous escape from the Munich Massacre, I was drawn to the tale for its depiction of the process of survival. I had grown up in a family of traumatized escapees from disaster and holocaust, and none of them ever found the vehicle that could deliver them from their ghosts. I was honored to offer my services to help build the transport for Dan’s journey.

At the time, I thought that my agenda would include an expression of compassion for the Palestinians. I was emotionally conflicted about Israel. While I understood the extreme importance of a Jewish homeland, I agreed with a close friend of mine, who used to joke that “They could ‘a’ just given us Miami.”

Frankly, Israel embarrassed me. My grandfather had coerced my mother into abandoning her dream of making Aliyah (moving to Palestine) in 1939, and he often compared Zionists to all the other Europeans who had grabbed land from indigenous peoples around the world. I believed that Israel should be forced to give back lands confiscated in the 1967 War, that Israel should take a more conciliatory stance.

My point of view clouded my perception of the Munich Massacre. Of course I never would have blamed the athletes for what happened, but I believed, like most Americans, that by disenfranchising the Palestinians and by discriminating against them, Israel was to blame by putting the athletes in harm’s way.

My point of view clouded my perception of the Munich Massacre. Of course I never would have blamed the athletes for what happened, but I believed, like most Americans, that by disenfranchising the Palestinians and by discriminating against them, Israel was to blame by putting the athletes in harm’s way.

I was committed to sharing Dan’s as a cautionary tale — watch out, world because this could happen again, and watch out, individuals, you could survive, and then you will realize that living through the ordeal was the easy part of it all. But I hadn’t considered the event’s other, more layered, implications.

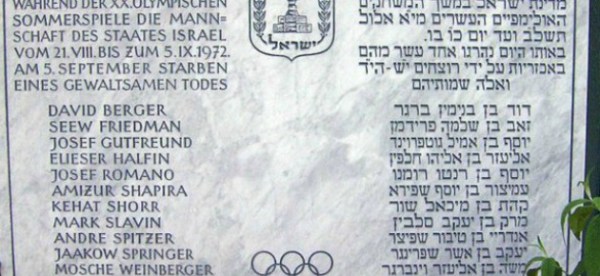

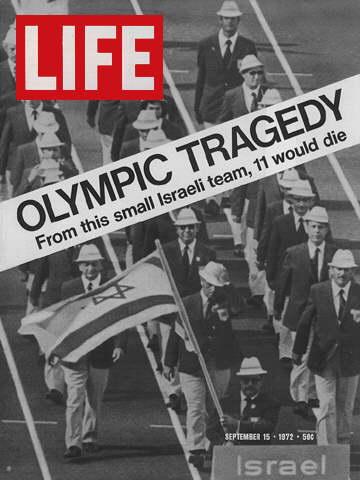

That there is no excuse for what happened in Munich is self-evident. A vile act of terrorism that usurped the sanctity of the Olympic arena and took eleven fathers, brothers, husbands, sons, nephews, cousins, friends from their loved ones cannot be justified or excused. The athletes were non-combatants, and their deaths were pointless wastes of fine lives.

The world clambered to give the terrorists the attention they sought. The masked murderers of Black September became fixtures on nearly every television set in the world, and when all was said and done, they were hardly so much as chastised. Until Mossad unleashed Operation Wrath of God, no real action was taken to so much as censure the perpetrators of the heinous violence; the Olympic Games themselves refused to skip a beat, carrying on as though nothing were amiss while half the hostages were strapped into helicopter seats and strafed with machine gun fire and the other half obliterated with an exploding grenade.

The message was clear. We may say the Olympics are on sacred ground. We may pay lip service to the precept that the Games are separate from the world of politics, but Israeli journalist Yarin Kimor was right when he pointed out that “The minute you raise a flag, it’s all about politics.” It was politically safer, more expedient for the IOC and world law enforcement agencies to just let this one go. It was too highly charged an issue. Take sides, and you rock the boat. Instead, eleven athletes were sacrificed. Nothing was really gained by the terrorists; the following year, perhaps spurred on by the Munich tragedy, the world — including the US, who had promised to defend its ally Israel — watched in silent complicity as Egypt and Syria attacked Israel on the highest, holiest day of their year. . . just as they had stood silently by in the 1930’s, when everyone knew what the Nazis were perpetrating against the Jewish people. Once again, the nations of the world stood by in hushed complacency and did nothing to lend a hand. In the peace negotiations that followed, however, the US took the role of “peacemaker” and threatened sanctions should the Israelis prove less than propitiatory.

The world seems to believe that Israel is expendable. Few seem to remember that less than 3/4 of a century ago, six million Jews died because they were unwelcome in the diaspora. There was no safe haven then. Even France, the country that first afforded citizenship to the wandering Jew, turned them out or fed them to the ruthless Nazi killing machinery; the US, my own beloved country where so many believe Jews to be firmly ensconced, denied entry to millions, despite the absolute knowledge that such denial meant certain torture and death to the shunned minions.

And there was no safe haven for the others who fell, like domino pieces, when no force prevented forfeiture of the Jews. Hatred swallowed up great numbers of Poles, gypsies, unmarried professional women, gays, physically and mentally challenged citizens, Catholic priests, et cetera ad infinitum.

Where will they all go the next time they are so endangered?

Forty years after Munich, the IOC continues to give tacit approval to the terror they allowed to happen. Yet another Olympic Games will begin without the simple Moment of Silence the victims’ families have consistently sought. The Arab nations call for the expulsion of Israel from the Games, and the IOC gives the same attention to that demand as they do to the request for the single minute of remembrance, a minute that says without words, “We are truly sorry. What happened here was despicable, and we will never let another athlete on any team be treated this way under our watch again.”

Forty years after Munich, the IOC continues to give tacit approval to the terror they allowed to happen. Yet another Olympic Games will begin without the simple Moment of Silence the victims’ families have consistently sought. The Arab nations call for the expulsion of Israel from the Games, and the IOC gives the same attention to that demand as they do to the request for the single minute of remembrance, a minute that says without words, “We are truly sorry. What happened here was despicable, and we will never let another athlete on any team be treated this way under our watch again.”

Worse, the world looks on bemusedly when Australian swimmers post photos of themselves going to the Olympics carrying, of all things, machine guns. Perhaps they are harmless idiots, these Aussies, but the message of the photo’s reception is that it’s okay to treat the massacre’s remaining family and friends as well as the athlete survivors with abject insensitivity. The world shook its head and tsikatched at the boys, but there was no statement from the IOC that what they had done was intolerable, that no such behavior would be conscienced.

Worse, the world looks on bemusedly when Australian swimmers post photos of themselves going to the Olympics carrying, of all things, machine guns. Perhaps they are harmless idiots, these Aussies, but the message of the photo’s reception is that it’s okay to treat the massacre’s remaining family and friends as well as the athlete survivors with abject insensitivity. The world shook its head and tsikatched at the boys, but there was no statement from the IOC that what they had done was intolerable, that no such behavior would be conscienced.

Munich Memoir: Dan Alon’s Untold Story of Survival is a first hand account of what it was like to be at the games when his friends, teammates, countrymen were taken and slain. It reminds us how easily a tragedy can happen in a garden of peace and love. It reminds us that we are all vulnerable, all candidates to stand one day as Dan did, in shoeless, shocked disbelief while people we care about are simply erased by others with a savage agenda.

It reminds us that we cannot ignore history. It will not go away. Let it be our teacher!